Heather Harris and Markus Cuff are two outstanding rock and roll photographers from different eras, with different styles, and with different specialties. But they both agree the way to handle a challenging and restrictive age in photojournalism is to let their lens find the truth.

The two well-known rock photogs were interviewed by author and radio host Nikki Palomino on her Whatever68 radio show last night.

Harris has shot some of the most interesting artists of our day ranging from punk rockers of the late ’60s to Glam Rockers and beyond — in big venues and small. Cuff is about rockers, music, motorcycles and tattoos, and his work is published in the top mags.

Both agree that while digital aspects and technology have helped improve the profession, restrictions at events, increased competition among publications, and declining media space has made the art of photography tougher than ever, for veterans and newbies alike.

Harris, who was first published in 1969, said the key for her initial success was hanging with the music writers and “UCLA Mafia” who all went on to make it in the business.

“Well I was always doing art drawing, since 3, I always drew from photographs. …When I was 12, I learned about copyright law and perhaps maybe I should take the photographs that I drew. In the meantime, in the early to mid ’60s, music was my life raft keeping me afloat, and when I started to go to concerts it never occurred to me not to bring a camera even though I didn’t have good cameras. I had a crummy Instamatic but I do have live shots of Buffalo Springfield. I went to art school at UCLA but never studied photography. I’m self-taught, I tried to figure out what the best people were doing. I knew I preferred the natural live look. I met people who helped me a great deal. I started getting published in around ’69 and hung around with a lot of music writers so I would hear about good things coming up.”

Those good things included groups like Iggy and The Stooges.

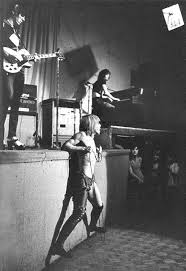

“I knew John Mendels(s)ohn, who was an excellent writer and he introduced me to The Stooges in 1970,” Harris said. “He was a bit of a contrarian so he liked anything that was disruptive, so that was a natural with him. And people forget that outside of Detroit and New York people didn’t hear of them and when they did they didn’t like them, so he was one of their early champions. but they didn’t come back to LA until ’73. That’s when I photographed them at the Whisky. I was still a poor college student so the only freebie I could get was a second show at the Whisky. If you could, imagine the difference between a first and second show at the Whisky in 1973, and all the photos you’ve seen that I took of The Stooges there were from a 22-minute, second set of two songs.

“I didn’t have much in the way of instruction, just tried to do it. I knew the looks I wanted; there’s a lot of people who are great photographers that I studied. I liked David Garr, he always to get always the natural light but always the emotion and his pictures looked different that everybody else’s.

“Other than that, I tried to photograph important music, music that influenced me. I have worked on staff at some periodicals.

Palomino asked: At the time, at the Whisky when Iggy Pop was playing, how was the audience?

“They were terrified of the band,” Harris said. “I have one great picture of Iggy hanging off the stage and there’s no one near the stage.”

Cuff, meanwhile was in a band and made his transition by coming up through the Guitar World, Guitar School, and motorcycle magazines like Easyriders and then finally Tattoo Magazine, where he’s been for 18 years.

“My first published work was in Guitar World and Guitar School, stuff like Flea and John Frusciante,” he said. Cuff found an interest in the motorcycle world when no one else was shooting bikes.

Like the musicians they cover, both photographers create their best work while taking a risk. Harris gave Palomino examples of bands who took a chance.

Mr. Twister, Harris’ husband, played in some theatrical proto-punk bands Chainsaw and Christopher Milk — bands that never get their due, she said.

“They say that the pioneers get all the arrows,” Harris said. “When it’s new not everybody gets it, I was very used to this from art history, where the best people in art aren’t necessarily known in their lifetime. The Stooges were like that initially. The bands my husband were in were theatrical proto-punk bands that influenced Cheap Trick, although they deny it now, The Tubes. But again they were amongst the first to do it so they’re not necessarily remembered. Although my husband was the first performer banned from the Troubadour for his performance … He had a very raunchy act.” READ HERE FOR MORE ON MR TWISTER, CHRISTOPHER MILK, AND CHAINSAW

Palomino asked, “So what do you see as far as changes in the bands now?”

“I’m told that the people who are younger than me don’t want to take risks. You have to be able to do it the way not everybody else is,” Harris said.

“The record companies don’t want to deviate from the formula. … I think they’ve forgotten the best experience for human beings incorporates all the senses you can, not just hearing… To be there and hear things that don’t show up even, in photos or in reviews that’s what you try to get, to add something to music.”

Cuff said what ticks him off are the rules like having to put down the camera after the third song a band plays, which is ludicrous.

“The technical aspects of concert photography have gotten better than ever. Nowadays you’re locked into two or three songs unless you’re kissing somebody’s ass. Now its so controlled, there’s no spontaneity.”

Cuff said after the management or venue stops photographs after the second or third song, he would go to the back and shoot with a long lens. Mainly because all the action happens after the third song, he said.

Harris said that’s one aspect of the business that has gotten out of control, so sometimes you have to beg forgiveness rather than ask permission.

“I try to to see if I can’t shoot bands where I can shoot the whole set. Sometimes it’s ‘Don’t ask, don’t tell.'” Harris said.

“I was there to do essentially what the musicians were there to do and that’s to get good art. When I started in the ’60s every publicist knew who every photographer was and photography was great publicity. Now it’s considered damage control.

“I know coming from fine art, how little it takes to really improve something. Go to a Rembrandt painting and look at the people and get very close and look at the eyes, there’s a red dot in the corner of each eye. It’s just a blob of paint but it makes the eye look watery and alive, it’s so little but has a good effect.”

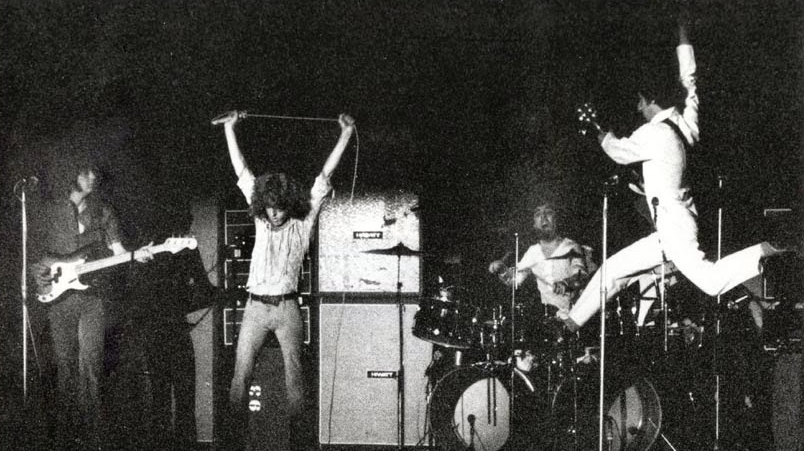

“I took a grainy picture of the Who at the end of their first Tommy tour in 1970 and it showed all four members doing exactly what they’re known for, leaping in the air, going nuts on the drums, twirling the microphone and, to me, even though it was grainy, it was perfect. That was the band. That’s as active as they were, that’s as exciting as they were. That was the band. Some people would say ‘Don’t you have any others?’ No they only made just one.”

Nowadays you could get off about 30 shots in the amount of time it took to snap that one, Cuff said.

Harris said the technology has improved photography.

“I don’t miss film because it was hard to deal with,” she said. “Working for magazines I don’t miss working in a cold dark room trying to make deadline,” she said. “And what they have now is better. Some people prefer film because it’s more hands on. I wish cameras I have now, way back then. The film i had to use to take that Who shot was called police film, even the instructions talked about the suspect rather than the subject.

As far as the intrusion of the Internet on how photographers sell their work, a proliferation of content from citizen-journalists, as well as the downsizing of magazines has hurt.

“In relation to magazines, Easyriders stopped a long time ago, I got with American Iron and then i have been with Tattoo for about 18 years. The tattoo world has been pretty rocked especially tattoo mags, by the tv shows and the ubiquity of tattoo magazines. When I started there were eight, max, decent tattoo magazines. Now there are now like 25 and they’re all called ‘Tattoo’ or some variation on that. There’s a lot of magazines, like Inked, a coffee table with a lot of girls in them. if there’s girls and they’re young even if the tattoo isn’t real good, eh it’s fine. So it’s a whole different world now. My work was always go around the country, go to shops and shoot their best work, and it was top shops, it was double-A tattoo work. Everything’s changed a lot because now, it’s the print world is really down and the tattoo magazines are trying to readjust to the digital platform.”

The nature of the picture has changed because the music has changed, Cuff said.

“How many pictures can you get of somebody wearing mouse ears behind a turntable?” Cuff asked. “A lot of those acts they may be fun to listen to … but you get two shots and you’ve got the whole thing. There’s a lot of strange anti-theatrical music out there now that’s not particularly photo friendly.”

“That’s why I like new bands that are good, they’ve figured out they want to do something different,” Harris said. “The history of art doesn’t go forward unless you take a chance.”