By AVA LIVERSIDGE

It happened. St. Vincent, our all-too-prim and postured rock God for the new age, has cracked. And what happened when her doll-ishness melted away? A rebirth marked by novel experimentalism and raucous intention. A new Annie Clark has been born.

Acquaint yourself with the train-wrecked master-mind. Annie Clark is realized in iconography — her image has been pinned loyally to her side since her breakout record. This could certainly be attributed to being a woman in a male-dominated industry, in a heavily male-dominated genre, playing a male-dominated instrument, but Clark has employed this to her advantage. She is not who you want her to be. This truth can be seen in the transience of her phases, in both sound and style, as it can be seen in the direction she has gone with new record, Daddy’s Home.

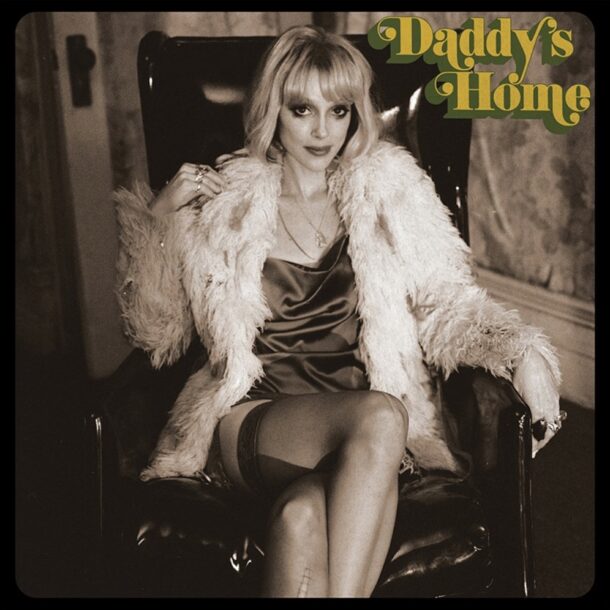

This is St. Vincent’s sixth studio album and, in name, a blatant reference to Clark’s father returning home from prison after serving nine years for stock fraud. Her look resembles a disheveled house-wife, crooked wig and all, marked by the tired eyes of someone who’s been left waiting too long. But this characterization is all too easy and all too precise for the singer that has long championed the glamorous mystique so tethered to rock-hood. Besides the title and the questions that may arise from it, her father plays a minimal role in the record’s narrative. The most explicit familial representation is in the title track, “Daddy’s Home,” whose groovy, fluctuating sonics paired with abrasive vocal repetition even distract from the lyrics’ self-elected focal point. This is masterful on Clark’s part and the way it should be. Once again, the rock star is undefinable to the masses, elusive, unhuman, to neither have nor hold.

The music is more sardonic than it is sulkish, in opposition to what her look would suggest, and the message is right there for listeners to interpret. She’s not hiding that. In a Youtube video explicitly explaining her lyrics and intention behind the feature single “The Melting of the Sun,” a song with already blatant lyrics that chronicle the strength of female musicians faced with adversity, while dressed in costume, lopsided platinum blonde wig, piano staged with Communist-era sheet music, and the jumping temperament of a hostage with a gun behind the camera, Clark sums up the paradox of Daddy’s Home: it’s basis is in artifice and the more she gives away, the more contrived Clark seems, and the more questions that arise. What would usually be a music scene misstep was transformed into a breeding ground for a whole slew of new contentions over Clark’s motivations.

As far as the new sound goes, Clark maintains the abrasive fuzz tone her guitar playing has become synonymous with, but the electronics weave through breezy early ’70s groove motifs; her vocals are another layer. The characteristic St. Vincent falsetto can be heard in choir-esque layers, but the majority of the vocals on Daddy’s Home are pure decadence — Clark waffles through phrases with a lilt dripping in honey. She’s golden, indulgent, and, above all, intentional.

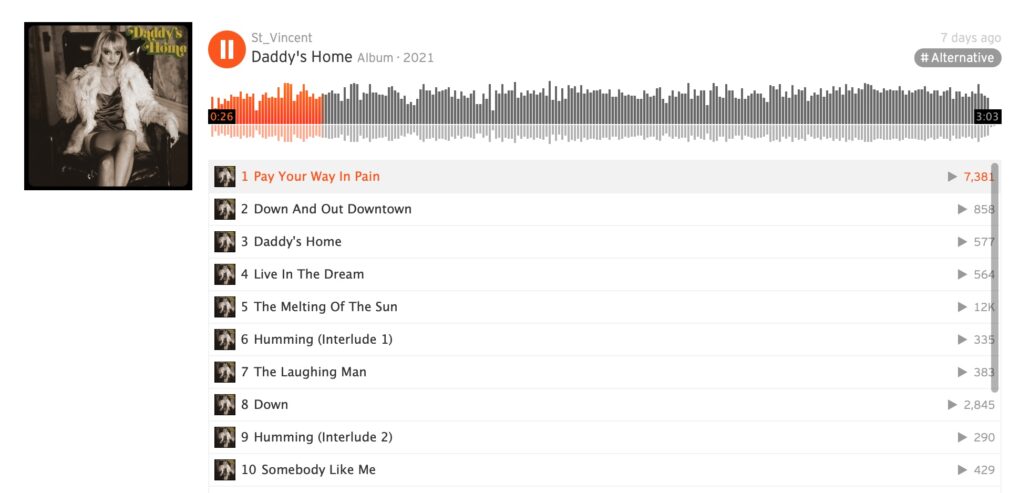

On lead single “Pay Your Way in Pain,” Clark repeats “I want to be loved” alongside the grim “Pay, pain / Pray, shame” moniker. On the taunting track “Down,” she’s already done wallowing and ready to take things into her own hands. As Clark’s clashing appearance and introspection may suggest, there are multiple moving parts constructing this new and fleeting era of St. Vincent-hood. But as her fastidious, manicured presence and press may also suggest, the dissonance has been her plan all along.

On “Down And Out Downtown” Clark reflects; “Digging through the basement of my past / It’s a long way back down.” St. Vincent’s relatively short, but complex and transient time in music has been marked by countless, sometimes untraceable movements through art and space. She is warning us of the complexities and confusions that may arise when trying to pin her down. “Humming (Interlude 1, 2, and 3)” pull the audience further down the rabbit hole with each round they play. Try to understand, characterize, and you’re bound to get confused. I suspect Clark suggests we bask in the madness and not concern ourselves with semantics.