By RICK SCHINDLER

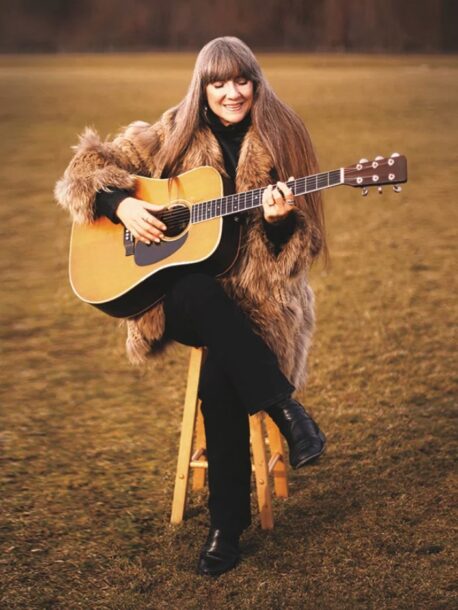

In 1970, Linda Hoover was a 19-year-old with some original songs, a pellucid soprano voice and a couple of talented unknowns in her corner: Walter Becker and Donald Fagen, who as Steely Dan would soon come to craft much of the decade’s pop soundtrack.

Hoover might have been the next Judy Collins. Even the title of the 1970 album she recorded with Becker and Fagen (along with guitarists Denny Dias and Jeff “Skunk” Baxter, early core members of Steely Dan) seemed to signal the scope of her ambition: I Mean to Shine.

But the music industry can be cruel: Due to a business dispute, the album was shelved. Becker and Fagen, composers of its title track, sold it to another singer (one Barbra Streisand), and Hoover returned to her parents’ home in Florida with nothing to show for a year of hard work except a quarter-inch tape of her unreleased debut.

I Mean to Shine finally got its decades-delayed release for Record Store Day. It is a carefully crafted collection of vintage folk-pop as well as an artifact of the origins of Steely Dan. In addition to writing five of the album’s 11 songs (Hoover wrote three), Becker and Fagen did all of its arrangements, which reveal early signs of the painstaking craftsmanship that in just a few years would become downright obsessive on Aja and Gaucho.

The opening title track, for instance, includes jazz-tinged horns (saxophonist Jerome Robinson and members of the Dick Cavett Orchestra perform on the album), but they’re unobtrusive; the focus is on Hoover’s voice. Barbra Streisand has a prodigious instrument, but Hoover is no slouch; she holds the final note for at least seven seconds before her vocal is faded out. I far prefer her straightforward interpretation of “I Mean to Shine” to the histrionic version on Barbra Jane Streisand (which deletes a bridge and alters some of the lyrics, too).

Also by Becker and Fagen, “Turn My Friend Away” displays Hoover’s upper range, while “The Roaring of the Lamb” (which appears on a number of Becker and Fagen collections but not on any Steely Dan album) has an anthemic chorus that showcases her vocal power, punctuated by a deft instrumental bridge. The melody is complex and sophisticated, and the lyrics teem with cryptic allusions that conjure that familiar Steely Dan feeling of having started a novel in the middle: Who are all these intriguing characters, and what have they been up to?

There are two other Becker-Fagen compositions. “Jones,” an acerbic tale of addiction, has lyrics like “one by one I let my days go by, getting high.” “Roll Back the Meaning” (which Fagen, Becker and Dias perform on You Gotta Walk It Like You Talk It, the soundtrack album of a low-budget 1970 film) has a light country flavor, augmented by agile guitar fills and three-part vocal harmonies.

“4 + 20,” a Stephen Stills composition from Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s 1970 album Déjà Vu, gets what may be Becker and Fagen’s most elaborate arrangement, including a long rhythm intro and plenty of horns, guitar licks and overdubbed vocals. “In a Station,” an ethereal song from The Band’s Music from Big Pink, substitutes saxophone and reeds for Garth Hudson’s clavinet. In contrast, Hoover is accompanied only by acoustic guitar and some gentle flute on the sincere folk ballad “Autumn.” It’s easy to imagine the song being covered by Judy Collins.

I Mean to Shine has been released on CD and digital on June 24, complete with the proposed original cover photo by Joel Brodsky, who went on to shoot dozens of iconic rock album covers The liner notes will include new interviews with Hoover and producer Gary Katz, who produced all of Steely Dan’s albums through 1980.